4/1/86, Tuesday

|

| Welcome to the Norma. |

After rounding up

the Escuela Nica students and

volunteers at the airport, the school representative dropped us off at a place called

Hospedaje Norma, a hostel like no

hostel I've ever been to. It looked like someone just gathered up pieces of

plywood and slapped them together to create partitions over a dirt floor. Each “dormitory”

contained three to six cots, a bare light bulb with a pull string to turn it on

and off and nothing else.

|

| Inside Hospedaje Norma |

Sanitary facilities

are minimal, as is access to electricity, even water is limited. I was surprised

and somewhat disturbed to find that there was only one aluminum tumbler set

atop a water jug for everyone in the hostel to drink from and that it was

barely rinsed between users because water is too scarce to waste on rinsing. Water

in that part of Managua is turned off two days a week (Mondays and Thursdays)

in an effort to conserve it, so a much-needed shower after the long, sticky

flight was out of the question because there was no running water last night.

Another surprise is

that there is no toilet paper to be found anywhere or at any price. I was told,

perhaps in jest, that La Prensa (the opposition’s newspaper) usually ends up

replacing it in the bathrooms. I don’t know if that’s what I've been using but

the squares of newspaper can’t be flushed, because they won’t dissolve as

easily as toilet paper so they must be thrown in a tin can located right next

to the toilet, making for a terrible smell coming from the latrines. The first

time I used the toilet, I automatically threw my paper into the bowl after

wiping, then panicked and scooped it out with my bare hands for fear of

creating plumbing problems for the whole neighborhood. To top that off, I

couldn't even wash my hands properly. The water that’s available for washing

our hands is no more than a trickle from a community jug and there was no soap

anywhere, so I was left feeling dirtier than ever.

|

| The "good" toilet (with a seat) at Hospedaje Norma. |

In the morning we

headed out to Esteli, about two hours north of Managua. We drove through the

countryside which was quite a contrast with the city. It was green, lush and

pristine – nature again proving its superiority over the man-made. We went

straight to the Nica school where we would have the opportunity to meet the

school staff, get to know our fellow students and later that afternoon, there

would be a small ceremony to introduce us to our host families.

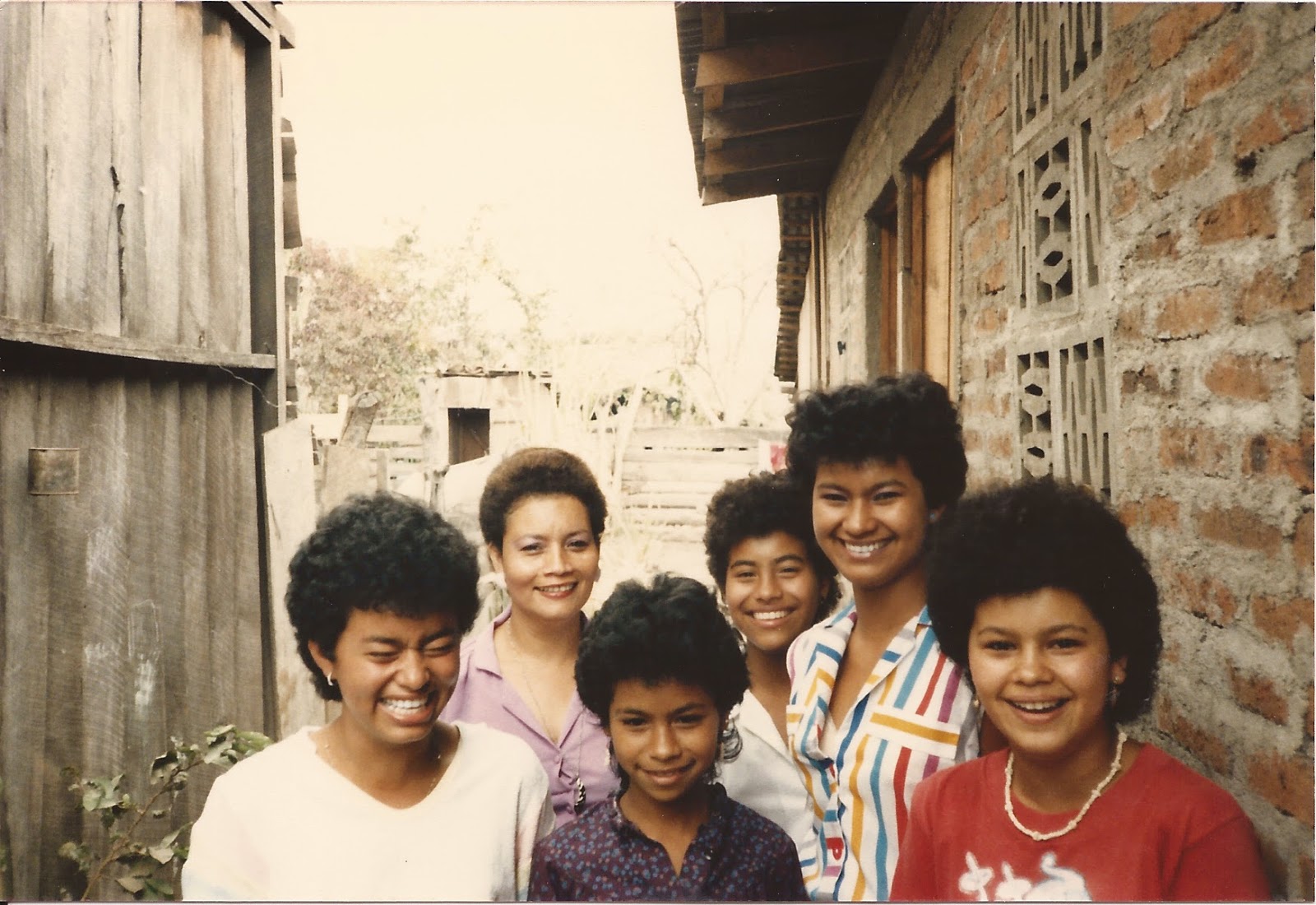

The introductory

ceremony was arranged so that we would feel as comfortable as possible with

families who would essentially be adopting us for the next month or so. I was

greeted by my “new” little sister Lissette, a young girl with close-cropped

hair and jovial, mischievous eyes. She has beautiful dark skin and a beaming

smile. She greeted me warmly and apologized for the fact that her mother couldn't

be there to welcome me.

|

| Lissette |

Lissette was

pleasantly surprised that I was not one of the students who had come to study

Spanish, my fluency immediately set her at ease and she began to joke with me.

I’m so glad they sent her, I can’t think of a more welcoming person. We walked

back to our house and Lissette insisted on pulling my wheeled suitcase through the

cobblestone streets of Esteli. Along the way she asked questions and pointed

out places of interest. By coincidence, we happen to have the same interest:

sweets!

“There’s a store

near your school that sells snacks and ice cream,” she informed me.

“Sometimes they

have banana splits. Have you ever had a banana split?”

“Yes,” I started to

say but she interrupted me.

“They take guineo and cut it in half and then they

put ice cream in the middle...” she proceeded with her enthusiastic description

but I was still back at guineo.

“What is guineo?” I asked.

“You don’t know guineo? It’s a fruit that’s long and

yellow and it tastes sweet and creamy...”

“We call that platano, or banana in English.”

“Oh, so you've had

it before?” she asked, crestfallen that she wasn't initiating me into the

delights of an unfamiliar fruit.

“Yes, but I

wouldn't mind having one with you,” I said, tossing her a side glance. Her

smile came back.

We’d gone about

five blocks when I noticed Lissette struggling with the heavy suitcase so I

asked for a turn pulling it. She resisted but finally gave in, shrugging her

shoulders and handing me the handle reluctantly, as though doing me a favor. I

became acutely aware of how many notebooks, crayons, pencils, markers, rulers

and erasers were in the overstuffed bag and I worried that one of the two

little wheels would give and break off. Now that her hands were free, Lissette

switched into full tourist guide mode, pointing out places of interest to her.

“That place makes posicle,

have you ever had posicle?” she

asked.

“No, what is it?”

“Oh, it’s hard to describe, I’ll have to bring you back so you can taste

it.” She gave me the smile of a kid about to put her hand in a cookie jar.

‘Very clever,’ I thought to myself, happy to have an accomplice. A

little further down the road, we passed a fresh juice bar which sells freshly

squeezed fruit drinks they call frescos,

along with pastries. Lissette’s face was full of expression as she described her

favorite treats. We were going to get along just fine.

Fun Size History: Banana Republic

Speaking of bananas, did you know that the banana was introduced to the United States in 1870? They were brought over from Jamaica and sold in Boston at a 1000% profit. The delicious, nutritious food soon grew in popularity, in part for its yumminess but also because of its cheap price. One could buy a dozen bananas for the price of two apples.

Before long, businessmen found that bananas became even more profitable when grown in countries where they could buy large plots of fertile land, clear them for banana plantations and then hire the now-landless farmers to work for near-slave wages.

A trio of companies, including the United Fruit Company (now known as Chiquita Brands) grew rich and powerful by exporting the bananas back to the United States for enormous profits. They formed mutually beneficial alliances with wealthy landowners in the host countries. They exerted enormous control over the governments of Central American countries and utilized the power of the U.S. military and C.I.A. to squash any attempted rebellions or uprisings. In 1954, the democratically elected president of Guatemala was deposed by the C.I.A. in a coup d’état at the request of the United Fruit Company. In Honduras, the United Fruit Company was known as El Pulpo - the octopus - because it had so many far-reaching military/political tentacles.

The term Banana Republic was coined to describe a fictional country but it is widely believed that Honduras provided the inspiration for it. Today the term is used to describe a small, politically unstable country whose government is concerned with growing the economy of a foreign or corporate entity, rather than the welfare of its own citizens.

And you thought Banana Republic was just a clothing company.

.jpeg)

.jpg)