|

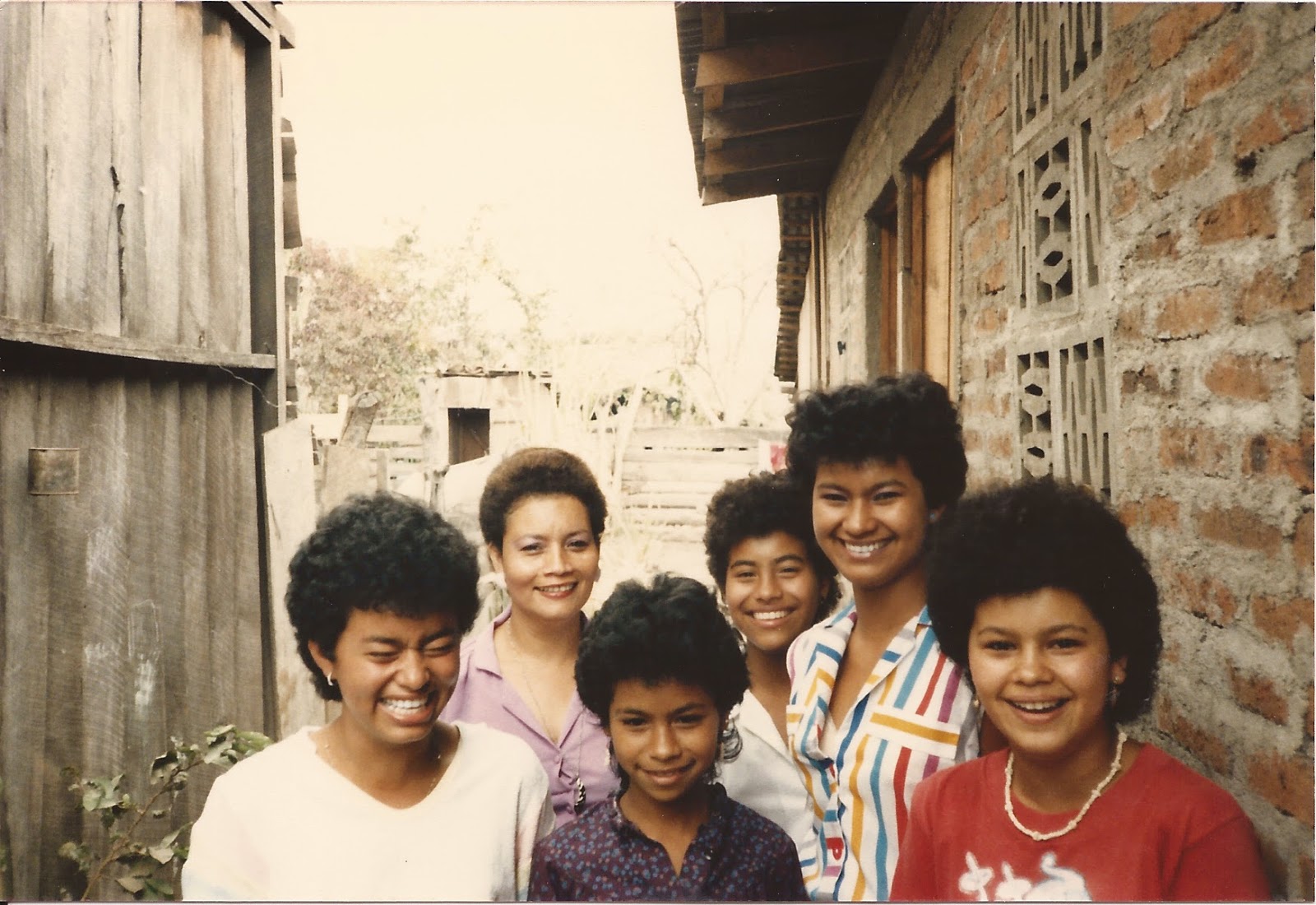

| My Nicaraguan Family: Front row: Paca, Milche, Carelia Back row: Francie, Lissette, Magda |

4/2/86, Wednesday

I wasn't able to shower in Managua and

last night it was too late when I finally got to our house in Esteli. Plus,

everyone wanted to get to know me and I wanted to talk to them, so I waited.

This morning I finally got my shower. It was a chilly experience. The water

never got warm so I took about a one minute shower, soaping up my entire body

before turning on the cold stream for a frigid rinse. Despite these things and

many other inconveniences of living with people at this level of poverty, I’m

very glad to be here. It’s not that big a deal to have to do without the

luxuries we have back home. Oddly, having to adapt so quickly makes me feel like

an alarm clock went off in my body and soul. It’s like my whole being took a

cold shower.

Yesterday I was introduced to my

Nicaraguan family. It’s an all female household. Five daughters live at home

and one lives in Managua. The girls all work together to manage the house until

their mom gets home from work.

Adrianna is the youngest of six daughters.

She’s quite thin, sweet, playful and soft spoken. She has a wild mane of messy,

curly hair. I’m guessing that she’s about 7 years old.

Next is Milche, she is only a little

older than Adrianna, she’s quiet, reserved, and very attentive.

Lissette, who picked me up yesterday

at the Nica school, is the middle daughter. I find her charming and outgoing...

a little rebel.

After that is Paca, she’s just a teenager

but she’s cultivated a maternal attitude towards the younger girls and they

definitely take direction from her.

Carelia is a beautiful, young high school

age lady. She’s not that interested in dealing with her younger sisters,

probably because she has a boyfriend named Lenin who Lissette says takes up all

of her time. (He already came by to say hello.)

Magda doesn't live at home, she’s the

oldest daughter. She’s married and lives in Managua.

My Nicaraguan mother’s name is

Francisca Dormus Zea but I heard one of the neighbors call her Francie and I

like that better. I mentioned the nickname and she insisted I call her that.

She’s in her mid to late thirties, a former guerrilla, with a stern

countenance. Yesterday, when she first walked up to greet me she had a serious look

on her face but it only took a couple of seconds for it to break into a smile.

She apologized for working late and it dawned on me that she was probably just tired. We

enjoyed a simple dinner of beans and tortillas and then she and I sat in the

living room to talk. She wanted to know everything about me but as I told it, I

found my story to be rather dull. I wanted to hear her story and after awhile

she shared it.

Francie is a strong, well-informed, intelligent

woman with incredible vitality. She’s part of a women’s military reserve

battalion but a lot of her time is spent doing what she calls social work. I

don’t know if she’s an actual social worker but it sounds like she’s mostly concerned

with the welfare of women, making sure their needs and interests are addressed.

As I listened to her, I could tell that she cares deeply about making sure that

women feel involved and participate in the revolution.

|

| Alice, Lenin and Francie |

“It would be very easy for women to

fall back into traditional roles,” she tells me. “Many of the women in Esteli

were active in trying to overthrow Somoza but to different degrees and in

different ways. For those of us who were

integrated in the struggle, it allowed us to see ourselves in a new way. During

the seventies, women combatientes were risking their lives, the same as the men

soldiers. We thought of ourselves as equals but even though we were doing the

same things they were doing, we still had to put up with machismo from other

soldiers, husbands, brothers...”

Her voiced trailed off and I wondered if she was remembering a particular

macho comment that might have wounded her. Francie sat quietly in front of me,

dressed in an olive drab shirt and pants. Her legs were spread open in front of

her in a pose that I had always associated with men, her body relaxed and open,

completely in control of her presence and ready to act at any moment. There was

a hardness to her look but a quality of gentleness in her eyes. I studied her

face, noticing her earrings and a hint of lipstick. I saw a woman for whom

strength and femininity were whatever she wanted them to be. She gazed off into

the distance for a minute, temporarily lost in thought.

I said nothing to break the silence. Finally, she sighed and smiled at me.

I wanted to know more about this matriarch but I instinctively knew not to pry.

My Nicaraguan family has been very involved (or integrated, as they say

here) in the revolutionary and post-revolutionary movements. They are a rich

source of history and firsthand information. Even the house we’re living in

seems to have a story to tell. It was used as a Sandinista headquarters and

some of the leaders lived here while in Esteli. We were still seated in the

living room when I happened to look at the painting that was hanging behind

Francie’s head. It seemed religious at first glance but there was something off

about it.

“Is that a picture of Jesus?” I asked, standing to take a closer look. The

lean, dark-skinned, bearded man in the painting had a rifle dangling by his

side but there was a look of peace emanating from his eyes and he appeared to

have a bright amber halo over his head.

No comments:

Post a Comment